Our First Edition!

New writing from Chloë Bass, Bryn Evans, Dessane Lopez Cassell, TK Smith, & Whitney Washington

3 Works

looking closely for 200, 400, and 600 words

Reloading distance in retrospect

Chloë Bass

As a form of preservation, I offer the following remembrance:

A plywood box, three panels long by three panels wide. One wall panel is missing, its absence an indication of an opening, or door. A single lightbulb hangs from a black cord extending from the upper right-hand quadrant of the ceiling, illuminating the space with warm concentration.

The ceiling sits two feet or more above my head. I have been offered a system of measurement as a form of poetry. I am not yet adept at using it. Or: both system and poetry are already within me, replicating focus as structure.

Outside of the box, echoing through the hush of the larger room, two voices begin a jokey banter about labor conditions. They are inside their workplace, guarding artwork from careless or unknowing visitors. I am inside an artwork. Three possibilities: a) I am not a threat; b) I am careful and knowing; c) they are unaware of my presence.

Relation, even unseen or unspoken, is its own form of creative interpretation. We are never simply living. We mediate through the lenses life presents, then make meaning.

I am alone. I am quiet. I am smiling.

Chloë Bass is an artist and the co-director of Social Practice CUNY. She is based in Brooklyn, NY. website || instagram

On Akea Brionne

Bryn Evans

Granda's profile curves toward an object of longing, his jeweled knuckles cradling a golden disk encased in a lighter substance, as if to keep the dish warm enough for savoring. His portrait fuzzes with soft distortions, like the fading details of a dream in those heady moments between sleep and wakefulness, or a memory that has been drawn and redrawn by someone else's telling: decades of mama's or grandmama's narration fabricating the photographed scene until it is certain. Granda’s gaze guides the viewer’s attention to the stilled choreography of his hands. His eyes appraise an evening meal while rugged fingers hold it gingerly, slowly guiding the food to his barely parted lips. What senses still remain and how do they blur with the passing of time? Is Granda’s looking another way to taste? And how much of savoring is attention? Viewing the moments before consumption, alternate readings of indulgence, of intimacy emerge. He is bowing his head, as if going in for a kiss.

Next to him, looking on, baby girl's poked-out pout, stuffed with whatever goodness had graced the dinner plate set before her, offers another meditation on close looking. She observes the scene, her tiny fingers perched on the edge of a platter. The child—no more than three, four—settles her attention on her Granda, gauging the speed of his movements, observing his focused gaze. Her lips pursed with rhinestones, engrossed in another lesson from the book of kitchen table pedagogy. She looks over at the man as if waiting for him to reach the other side of their shared sustenance, his slow motions modeling for her a new word: delicacy.

This free-hanging textile diptych, featuring a digital image woven onto jacquard and embellished with rhinestones, makes possible a spatiotemporal landscape where there are no finite borders but abundant space to reflect on ancestral communion. Akea Brionne's Dinner with Granda (2023) centers on a young Brionne sitting at the dinner table with her maternal grandfather, their bodies framed in two distinct textile objects. The work presents an intimate window into the New Orleans-born artist's familial archive, revelatory in the same way an old family photo might make known a shared likeness with a beloved elder, as evidenced through a simple hand gesture, facial expression, or hair style. Three neat cornrows angled just so, toward the patriarch’s tanned scalp, her young crop resembling his parted cloud of pearls.

Bryn Evans is a poet from Atlanta, Georgia. instagram

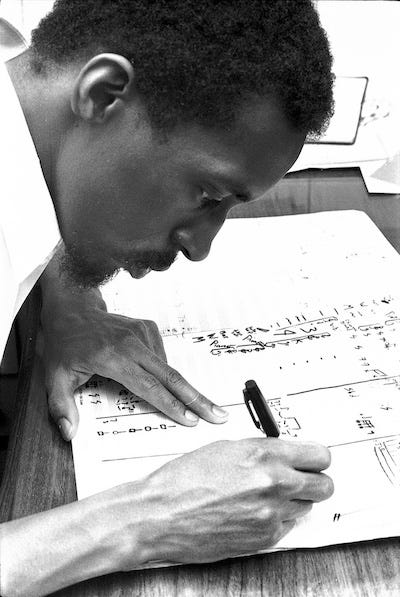

Double Armor: On Julius Eastman

Dessane Lopez Cassell

In 1979, the composer, choreographer, and performer Julius Eastman threw down a few gauntlets. In a piece for Ear magazine, titled “The Composer as Weakling,” he surmised, “To be a composer is not enough.” In his view, “she must become an interpreter, not only of her own music and career, but also the music of her contemporaries, and give a fresh view of the known and unknown classics.” In essence, Eastman—an under-recognized titan who bridged the Uptown/Downtown, classical/contemporary music divide—was calling for artists to become full participants in their own ecosystems; to take on the work of critics, performers, composers, and scholars all at once. No more languishing in the isolation of the studio, waiting for recognition. And while the moniker of “multidisciplinary artist” abounds today, Eastman was ahead of his time in walking the walk.

That same year, Eastman released a trio of works composed for four pianos—“Gay Guerrilla,” “Crazy Nigger,” and “Evil Nigger”—today regarded as some of his greatest (and most infamous) works. Each purposely incendiary title epitomizes Eastman’s matter-of-fact style of defiant mischief. Debuting the works at Northwestern University in January 1980, he explained,

The reason I use that particular word is, for me, it has what I call a basicness about it. The first niggers were, of course, field niggers. Upon that is the basis of the American economic system. Without field niggers, you wouldn’t have the great and grand economy that we have. That is what I call the first and great nigger. What I mean by nigger is, that thing which is fundamental.

He makes an apt point. American wealth was built on racial subjugation and chattel slavery, and their modern forms—prison labor, racist lending practices, the evisceration of DEI measures, to name a few—continue to sustain it. Regardless of whether the word is shot out as a slur or uttered colloquially among kin (e.g. with a softer “-a”), it’s often associated with baseness, denigration. It follows then that Eastman, an out and proud gay, Black artist deeply concerned with the political and physical potential of music would combine it with “crazy” and “evil.” Each composition’s title becomes a double negative, a hyperbole that stands in for perceptions of Blackness.

Beholding “Evil Nigger” myself recently, I’m struck by what feels like the composition’s defiant heartbrokenness. It’s currently being presented as part of Julius Eastman & Glenn Ligon: Evil Nigger, at 52 Walker in New York. A framed, blown-up copy of the score hangs opposite the gallery’s entrance, beckoning visitors in as a prelude to the exhibition’s centerpiece: a four-piano installation, three of which are self-playing and thrum with an MIDI arrangement of Eastman’s composition. While the installation itself feels like a bit of a cheap trick—heavy-handed even, as a gesture to a late musician known for having his own ghosts—it’s hard to dilute the raw power of “Evil Nigger” playing out loud at the top of every hour. The composition rips open at a blistering pace, filling the silent art space with a boisterous melancholy. Yet it’s more irreverent than despondent, pulsing as though bucking a smothering weight. As Eastman’s brother Gerry has noted, “[Julius] had to have double ‘fuck you’ armor to survive.” Likewise, the critic-composer Kyle Gann has referred to Eastman’s music as “some of the most angry and physical minimalism ever made.”

“Evil Nigger” is exemplary of Eastman’s theories of “organic” music, an additive process of composition, in which continually repeated ostinatos (or musical phrases) are layered over previous ones, which then eventually drop out. Its effect is almost bewitching.

Throughout its roughly twenty-two minute duration, I walk back and forth and around the installation (in part because there is no seating). I find myself thinking of the artist Jenny Odell’s writings on attention and duration. “It’s a lot like breathing,” she explains. “Some kind of attention will always be present, but when we take hold of it, we have the ability to consciously direct, expand, and contract it.” Attuned to such maneuvers, my attention stretches like the tentacles of a squid, suctioning up Eastman’s deeper, more boisterous notes and pulling them close. I swallow a wave of unexpected grief. The progression tugs at me, until a well of emotion begins to seep out. Alone in the gallery on a frigid winter morning, I find myself weeping silently.

"What I am trying to achieve is to be what I am to the fullest: Black to the fullest, a musician to the fullest, and a homosexual to the fullest," Eastman once remarked. Enveloped and overwhelmed by his expressiveness, I can’t help but smile. A catharsis I hadn’t been able to admit I’d needed rumbles out of my chest and pools at my feet.

Dessane Lopez Cassell is a New York-based writer and editor whose work focuses on the intersections of art and film. instagram.

Tough But Fair

let’s talk about things we don’t like

If You Want Black People’s Money, Just Say That.

TK Smith

What I find both insidious and comical about the co-opting of liberation terminology by cultural institutions is how shallow and performative the use of that language can be. Insidious, because this co-opted language can be used to secure external funding and the trust of audiences misled to believe that the institution is aligned with their values. Comical, because the co-opting agents often use these terms without much if any understanding of what they mean; demonstrating no understanding of cultural context, no interest in nuance, and no exploration of critical theoretical frameworks. Instead, they misuse these terms so boldly that one can’t help but laugh. If you just want the resources you can glean from Black audiences, just say that, and say it with your whole chest.

A frequently abused term is “decolonize,” which has been engaged superficially by museum professionals who believe the mere presence of a Black artist can undue centuries of colonial violence and/or they underestimate their audiences as too ignorant to understand how colonial violence is structural and reinforced by monolithic boards, problematic funders, violently ambitious directors, and bad curators. Said museum professionals also use terms like “justice,” “healing,” and “reckoning” to then invite Black artists, scholars, curators, and even community partners into their institutions through temporary projects, assuming audiences will be satiated with one show, one program, one Black face (we love a jazz night at the museum).

An institution’s failure to seriously engage with liberatory terminology, practices, or pedagogies, especially those created by Black, brown, and queer peoples, creates a culture where these marginalized artists, regardless of how established and successful they may be, risk sacrificing critical engagement with and/or true appreciation for their work in order to gain the visibility (canonization) and life sustaining resources (money) seemingly offered by museums. Black audiences are, in turn, subjected to subpar exhibitions (beautiful gowns, beautiful gowns) and insufficient scholarship because we want to support artists from our communities and/or because we simply want to see a bit of ourselves reflected on the walls. It does not serve us when you pretend you are invested in our liberation. Co-optors of liberation terminologies don’t want to decolonize, they want good optics—and they are only concerned with good optics because it once led to more funding. What will be most telling of the integrity of these cultural institutions and museum professionals is if they continue appropriating liberatory terms under the current political regime, where we are witnessing rapid divestment from DEI initiatives and programs.

TK Smith is a curator, writer, and cultural historian. website || instagram || linkedin

Report From the Field

intimate looks at unexpected art worlds

Whitney Washington taps in from Huntsville, Alabama

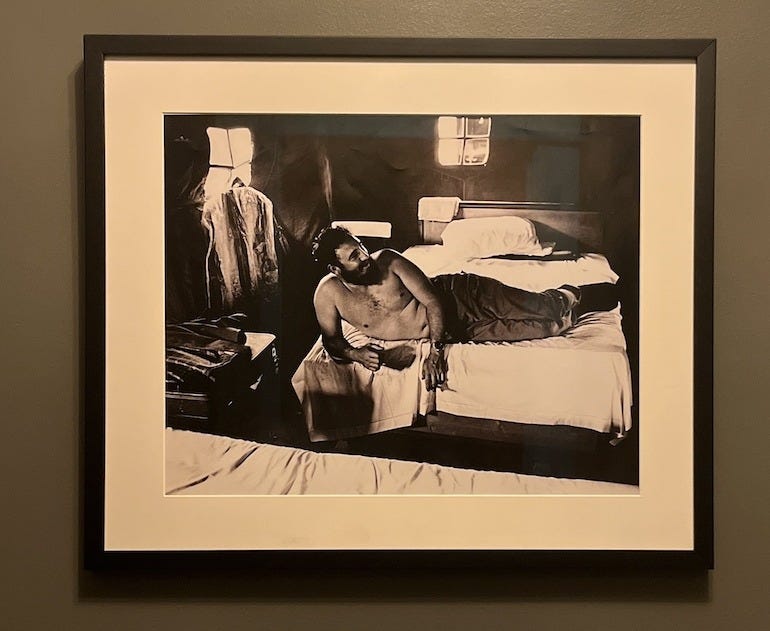

Great, impactful art can be found in the most unexpected places—like a friend’s bathroom wall. A friend from my writing group is the daughter of accomplished photographer, Truman Moore, and his photos are hung around her house. Sitting on her toilet a couple of weeks ago, I was surprised to see this photo of a very cozy Fidel Castro.

Without a doubt, the place to go for contemporary art in Huntsville is Lowe Mill, a factory-turned-arts space. In one of their galleries, folk artist Church Goin Mule’s paintings offer a reflection of traditional Southern art and sentiments. Their paintings are often flanked with Biblical or homespun phrases like “Change is all around us. Change is all within us.” In the industrial gallery space, my mother took a moment to sit to observe the mules.

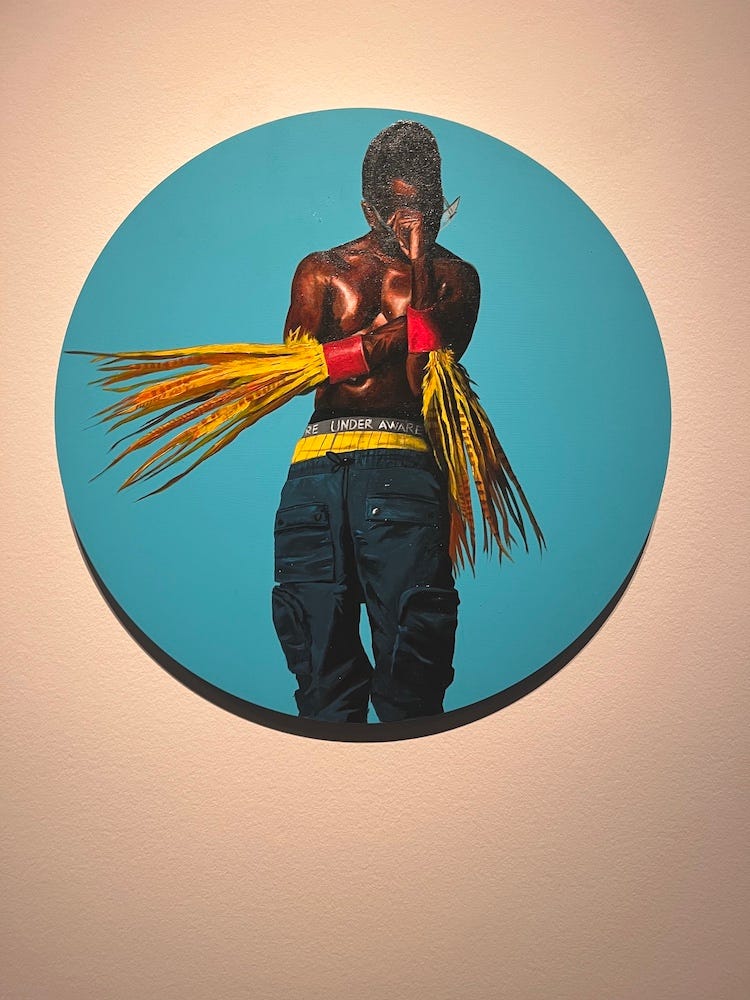

At the Huntsville Museum of Art, Fahamu Pecou’s vibrant, hyperrealistic paintings contrast contemporary Black cultural artifacts like sagging pants with traditional materials like feathers to create something as dynamic as “Birds of Paradise” (2023). The HMA has broadened their scope of exhibits in the past few years, from more traditional or regional shows for largely white audiences to more inclusive, youthful, and dynamic shows today. Although limited in their capacity for traveling exhibitions due to size and budget constraints, the museum is branching out into new genres.

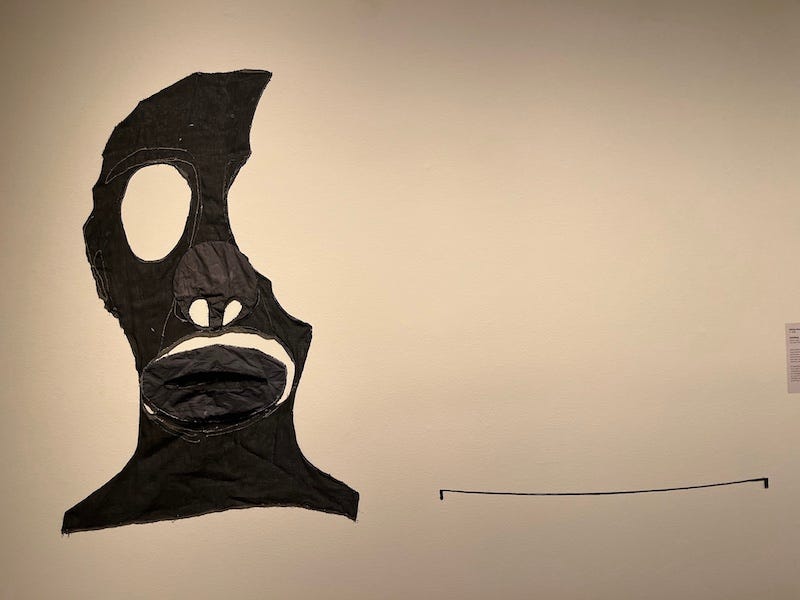

Alicia Henry’s joint show with Pecou debuted in October 2024, and was an incredible get for Huntsville’s growing arts scene. Sadly, just weeks later, Henry passed away. It was profound to experience the show in a new way, as a legacy being created in real time. Henry’s work with fabric is deceptively layered, as seen in this Untitled piece from 2022. The large quilted mask evokes so much as a viewer: Blackface, a gimp mask, the comfort of a grandmother’s quilt, a cartoon. And the single string to the side reminds the viewer of Henry’s work which will now forever be unfinished.